Otto Donald Rogers, who died on 28 April 2019 at the age of 83, was one of Canada’s most original modern painters and arguably the most inventive to come out of the prairies.

He served as a member of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of Canada, as well as on the International Teaching Centre at the Baha’i World Centre. In a letter mourning his passing, the Universal House of Justice wrote: “Unstinting in his efforts to serve the Faith and with great accomplishments to his name, he remained a man of humility and selflessness, gracious and gentle.”

Memorial gatherings were held in his honour around the world, including at every Baha’i House of Worship.

Rogers was born into a farming community on 19 December 1935 in Kelfield, Saskatchewan. The expansive skies and endless horizons of the landscape had a profound effect on the young Otto. He would take himself off on solitary walks, fascinated by the physicality and elusiveness of the vistas. “These daily trips were as much a journey into the mind as they were over prairie earth,” he later wrote. “The view in every direction was endless and, as to education, the confined single room could not compete with this infinity. I was suspended in time and space and took constant delight in the diversity of color and form.” Such visual contrasts—between proximity and distance, opacity and transparency, human activity and the immensity of space—would all find expression in Rogers’ painting.

But Rogers never considered himself a “prairie artist” as his interests grew to encompass a profound spiritual sensibility. A review in the Globe and Mail in 1988, observed that the roots of his painting, were “sunk much deeper into the soil of spiritual quest that nourished the early twentieth century abstractionists than into the soil of the artist’s native Saskatchewan…But all his windows open in that direction, toward more mystic prairies washed by spiritual rains.”

Rogers was first introduced to art by chance at the Teacher’s College in Saskatoon. Displaying a raw, rare talent, that was encouraged and nurtured by the landscape artist Wynona Mulcaster (1915-2016), Rogers felt that he had found the means by which he could express his inner dialogue. He went on to study art eduation at the University of Wisconson, Madison, receiving a Masters in Fine Art in 1958.

Apart from a brief four-month stay in New York City in 1958, he was to remain in his native province, returning in 1959 as a member of the arts faculty of the University of Saskatchewan until 1988, including serving for four years as head of department. Former students recall him as a “charismatic teacher”, “a fantastic mentor, a task master with very high standards.”

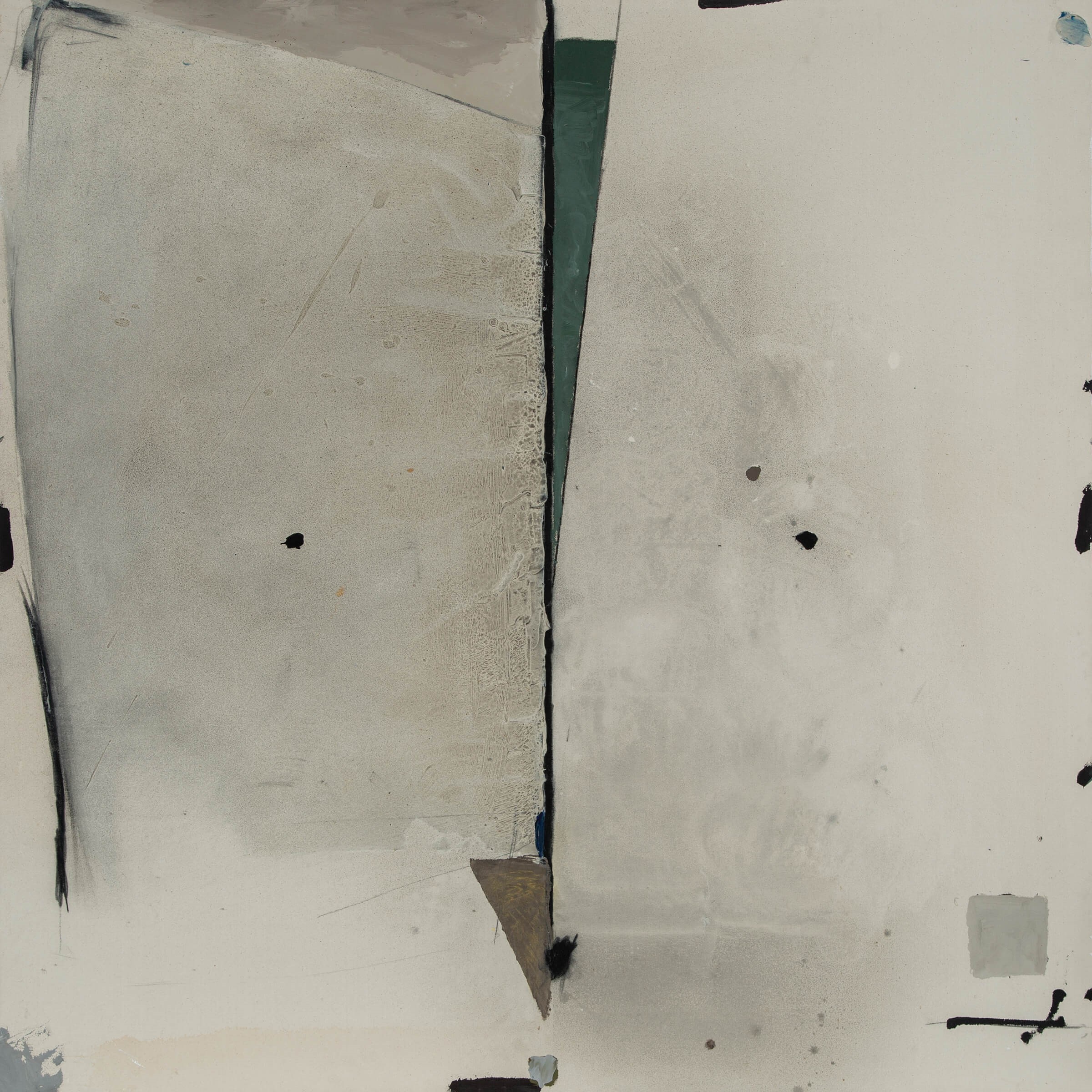

Rogers’ early works evoke elements of the prairies without resorting to any literal pictorial representation. There were also portraits, still life paintings, and cityscapes. Yet, while he moved ever more decisively towards a non-referential abstraction, he recognized that his paintings maintained “a memory of still-life and landscape.”

A pivotal event in both Rogers’ life and his art had been his acceptance of the Bahá’í Faith in 1960. The religion’s main principle of unity became central to his creativity. Great works of art, he believed, should achieve a harmonious conversation between all of their component elements. When that was successful, the painting acquired “spirit” and could have a profound effect on the viewer. “To me the purpose of art is to elevate the human soul,” he said.

Another of the Bahá’í teachings, that the individual must independently seek after truth, led Rogers to realize he had a “terrible necessity for search…a passion for the unknown.” He described himself as on a “quest” to “be at liberty to move to an unknown destination.”

Throughout his long career, Rogers’ work was a constant exploration of questions of art and of nature, of the creative dynamic, of language and consciousness, of the relationship of diversity to unity. He believed that to enter the world of faith was a prerequisite to the creation of an enduring art which was a manifestation of both heart and mind—a heart, he said, that turns towards the essence of creation and a mind that conceives visual order.

In the latter case, many of his compositions are more akin to architectural form than painting. “What the architects are doing I find more interesting than most painters,” he wrote. “Good architecture has a formal integrity that contemporary painting and sculpture too often lack.”

Rogers won many awards for his painting, sculpture and graphic arts. His work is held in public and private collections in several countries, including the Art Gallery of Ontario; the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Barcelona; and the National Gallery of Iceland.

An inspirational speaker and promoter of Bahá’í teachings, Rogers was invited to serve his faith at an international level, relocating to the Bahá’í World Centre in Haifa, Israel in 1988. Among his numerous travels over the ensuing ten years, he visited the newly opened Soviet Union and met with previously banned artists. He was conducted through the vaults of the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, where he saw the works of such painters as Kandinsky and Malevich.

Rogers’ responsibilities in Haifa left little time for painting on a large scale. Instead he produced more works on paper. These constructions resulted in a more fluid abstract pictorial language which continued on his return to Canada in 1998. He and his wife Barbara settled on the shores of Lake Ontario in Prince Edward County, where he set to work in a studio, purpose built by their son-in-law, Siamak Hariri.

Constantly self-critical and challenging the tendency of many artists to become complacent with a successful formula, Rogers constantly set new pictorial problems for himself to resolve. Continuing to paint every day into his 80s, he was determined to make each work as aesthetically excellent as he could.

Aside from his prodigious talent, Rogers was a man of great warmth, thoughtfulness and integrity with a disarming sense of humour. He is survived by his wife Barbara, and three surviving children, Klee, Sasha and Julie.